The Prediction Markets We Were Promised: A Guide to Slaying Dragons With Oracles, Commitments, and Blockchains

In this post we'll walk through the inner-workings of prediction markets and the systems they exist inside of.

Prediction markets have circulated as a promising application of blockchains since at least 2013, where they were briefly mentioned in the Ethereum whitepaper. Shortly after, in 2014, proposals for decentralized prediction markets re-emerged concurrently in two orthogonal architectural lineages—systems run by automated market makers (AMMs) that provide always-on pricing and liquidity, and systems powered by order-book markets that rely on explicit bids and asks. Ever since, the ecosystem has produced a long tail of variants, hybrids, and reinventions (see, e.g., Appendix A here for a list).

Despite this line of work, the dominant paradigm adopted by today's prominent prediction market platforms have been converging towards increasingly more centralized, more permissioned, and more trust-based systems. In the most popular platforms (e.g., Polymarket and Kalshi), the systems' critical levers—market creation, liquidity provision, outcome resolution, and settlement—remain subject to human discretion or governance that can be influenced after positions are established and exploited during market operation at users' expense.

The real-world manifestations of this "killer crypto-native dApp" we've talked about for over a decade have seemingly hit the mainstream, but they've completely diverged from the core thesis that made pairing prediction markets with blockchains so enticing. If prediction markets are meant to be effective mechanisms that users can wield to aggregate information from disparate sources, then this trend away from the decentralized prediction markets we were promised isn't a design detail—it’s a dead end.

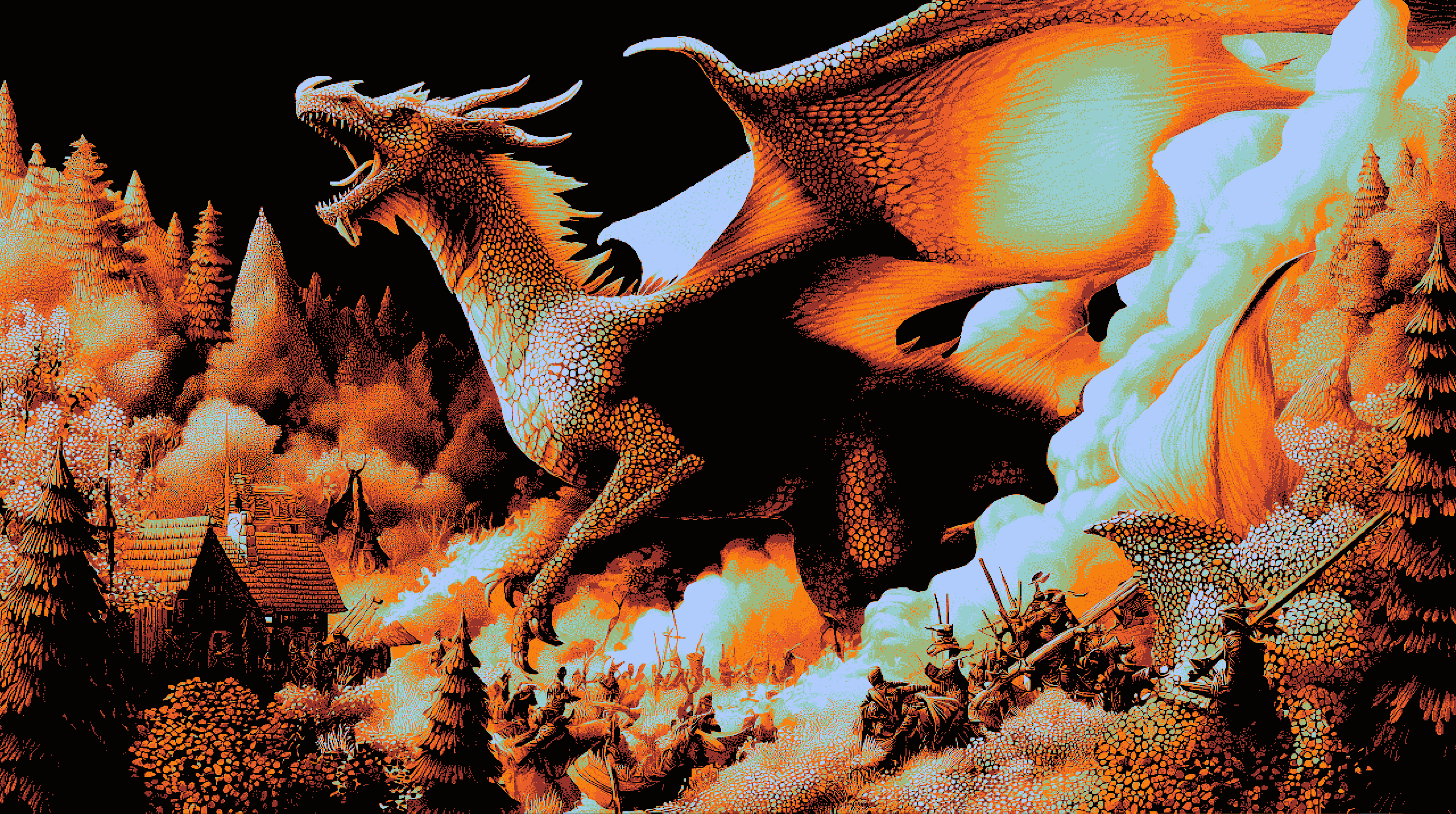

In this post we'll walk through the inner-workings of prediction markets and the systems they exist inside of. We'll show that building truly decentralized, permissionless, and trustless prediction markets is full of dragons. Our goal is to chart precisely where these dragons live, why existing platforms keep sailing around them (or have fallen prey to them), and why we may finally be able to slay them due to a confluence of recent technological advances.

This post kicks off our journey, but the final destination is still on the horizon. Over the coming days we'll release a series of posts that tell the whole picture. We've split the story into five pieces:

- Part I: What Are Prediction Markets?

Here we define prediction markets and the problems they're designed to solve. Our introduction is kept at a high-level, and only digs into technical details that'll help understand or build intuition for discussions later on. Beyond abstractions, we also highlight certain facets of prediction market platforms that are critical for understanding how prediction markets exist in reality. - Part II: The On-Chain Prediction Market Thesis

Prediction markets have been in the collective imagination of people building blockchain technologies for over a decade. In this part I try to unpack why on-chain prediction markets are so enticing, and what properties we need to ensure for the vision to hold. - Part III: Praxis and the Illusion of Progress

Popular prediction market platforms already exist, and are increasingly entering mainstream discourse. Are we on a trajectory that leads back to the thesis we envision? Or are we converging on something else? From the title of this part, you can imagine I argue the latter. The goal of isn't to criticize any individual platform; it's to identify the dragons we need to face and the traps we need to avoid when building prediction market platforms. - Part IV: Survival and a Need To Redefine Monetization

From the perspective of making revenue, the model adopted by prominent platforms today is "successful". However, is it aligned with supporting accurate prediction markets? I argue here that the answer is "No". It's aligned with supporting prediction markets that maximize volume and volatility. We discuss an alternative approach, wherein platforms stop behaving like venues and instead monetize as infrastructure. - Part V: Returning to the Thesis

Finally, after a long journey, we circle back to the original question. How do we build the prediction markets we were promised? In this part I illustrate how a set modern tools—scalable chains, oracle games, verification protocols, and AI—could be brought together to make the thesis a reality. Discussions are kept at a high-level (honestly, each subsection could've easily filled its own series of posts...) and the claim is not that the path forward is easy. Instead, I argue that we finally have the necessary ingredients and can reasonably start building platforms aligned with prediction markets we were promised. A strategy, some grit, and the resolve to innovate is the final barrier in our way.

Part I:

What Are Prediction Markets?

Suppose you (the aggregator) would like to obtain a prediction about an uncertain variable, and you suspect there exist individuals (informants) out in the world who hold private signals bearing on the eventual outcome. How should you go about eliciting and aggregating relevant signals from disparate informants into a single coherent prediction? How should informants reason about revealing their high-quality, and perhaps only partial, information? How do we incentivize strategic informants to reveal private information honestly? These questions have been studied extensively in the field of mechanism design under the umbrella of information aggregation problems, and prediction markets are designed to solve these problems by making "being correct" tradeable.

Informally, prediction markets work as follows. The aggregator defines one or more contingent claims (i.e., securities, contracts, or assets) whose payoffs depend on the realized outcome being predicted. Informants then trade these claims however they please. When the prediction market is well designed, each trade has a concrete interpretation as an implicit report of the trader's belief and the mechanism yields a collective forecast the aggregator can read off directly.

The remainder of this part is dedicated to laying some groundwork we'll need later on. Readers who primarily want a broad-strokes understanding of our arguments, or who've engaged with formal treatments of prediction markets, can skip to Part II without too many worries. Our discussion is tailored towards setting the stage and providing slightly more formal intuition that could help.

Specifically, below we'll define prediction markets a bit more rigorously, introduce common market microstructures (i.e., the trading/price-formation mechanism), and highlight some key platform-level decisions required for these markets to function.

Arrow-Debreu Securities

For the sake of clarity, and to keep discussions concrete, much of this series will focus (sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly) on prediction markets for Arrow–Debreu (AD) securities. This is the canonical setting users of today's popular prediction market platforms will typically have in mind when reasoning about what prediction markets do: Contracts pay 1 if a particular outcome occurs and 0 otherwise, so the market price can be read like a probability over outcomes. With that said, although some specific technical details may need to be massaged or extended, the overarching arguments we'll make throughout the post can be applied to more general classes of prediction markets.

Let \(\mathcal{Y} = \{y_1, \dots, y_n\}\) be the set of mutually exclusive outcomes the event could take, and let \(Y \in \mathcal{Y}\) denote the realized outcome. A prediction market for AD securities has \(n\) assets \(A_1, \dots, A_n\) that informants can buy and sell, where each share of \(A_i\) pays 1 unit of currency if \(Y=y_i\) and 0 otherwise. If an informant’s belief assigns probability \(q_i = \Pr[Y=y_i]\), then in an idealized setting (no discounting, no frictions, etc.) their expected value of one share of \(A_i\) is \(q_i\) and their "fair price" for \(A_i\) should therefore be \(p_i = q_i\). Hence, assuming traders make decisions accordingly, the current market prices \((p_1,\dots,p_n)\) are naturally interpretable as a collective probability distribution over \(\mathcal{Y}\).

From this understanding of how "price \(\approx\) probability" we're able to derive why market incentives turn trading into a channel for directly reporting beliefs when informants are strategic. If the market currently prices \(A_i\) at \(p_i\) and you believe the true probability is \(q_i\), then buying one additional share has expected profit \(q_i - p_i\) (and selling has expected profit \(p_i - q_i\)). In idealized settings a trader's best response strategy reduces to simply: buy when the market price is below your belief, sell when it is above, and stop when prices match your belief. Obviously, in practice, prices will deviate from traders' exact probabilities due to complexities such as risk aversion, fees, etc. that'll inevitably exist. Our goal shouldn't be to design systems that match these theoretical ideals exactly, but to build systems that aspire towards them; to that end, I believe a well-designed prediction market makes moving prices toward your belief the natural profit-seeking action rather than outmaneuvering other traders or exploiting systemic inefficiencies.

A Concrete Example:

In a competition with \(n\) competitors, \(\mathcal{Y}\) could be the set \(\{\)"Competitor 1 will win"\(, \dots,\) "Competitor \(n\) will win"\(\}\) and \(Y\) will take on a value in \(\mathcal{Y}\) corresponding to who ultimately won the competition. For each \(i \in \{1,\dots, n\}\), informants buy or sell shares of \(A_i\) depending on their belief about what \(Y\) will be. At the end of the competition, when it's been determined that competitor \(i\) won, we know \(Y=\)"Competitor \(i\) will win" is true so each share of \(A_i\) pays out 1 unit of currency whereas each \(A_{j \neq i}\) pays out 0. In the end, informants with well-calibrated beliefs are expected to profit.

Market Microstructures

Prediction markets aren't a monolith, they're better thought of as a family of mechanisms whose behaviours can vary dramatically depending on the market's microstructure—i.e., how the prices are set, liquidity is provided, and trades are executed. For the purposes of this series we'll compartmentalize these design decisions into two archetypes:

1) Cost-function Prediction Markets

A cost-function prediction market (CFPM) is driven by a convex cost function \(C:\mathbb{R}^n\to\mathbb{R}\) derived from a market scoring rule, and is equivalent to popular classes of AMMs used in DeFi. CFPMs maintain a market state \(x \in \mathbb{R}^n\), where \(x_i\) is the net outstanding shares of \(A_i\). If a trader wants to buy/sell a bundle \(\Delta \in \mathbb{R}^n\), their "cost" to move the market from state \(x\) to \(x+\Delta\) is given by \(\text{cost}(\Delta\mid x) \;=\; C(x+\Delta) - C(x)\). The instantaneous market prices are given by the gradient \(p(x) = (p_1(x), \dots, p_n(x)) = \nabla C(x)\), which (for appropriately chosen functions \(C\)) provably live on the probability simplex (i.e., \(p_i(x) \ge 0\) and \(\sum_i p_i(x)=1\)). As a result, CFPMs ensure you have a continuously defined probability vector (and hence well-defined prices) at all times—crucially, even when no one is trading.

The relationship between CFPMs and proper scoring rules also guarantee that, under standard economic assumptions, traders' expected profit is maximized by trading until prices match their true belief. That is, the mechanism makes "moving the market toward what you believe" the locally optimal behavior while simultaneously ensuring your target always exists and is well-defined.

A Canonical Example:

Perhaps the best known CFPM is the Logarithmic Market Scoring Rule (LMSR), where \[C(x) \;=\; b \log\Big(\sum_{j=1}^n e^{x_j/b}\Big), \quad\text{so that}\quad p_i(x) \;=\; \frac{e^{x_i/b}}{\sum_{j=1}^n e^{x_j/b}}.\] The parameter \(b>0\) controls liquidity/price responsiveness, where larger \(b\) makes prices move more slowly (deeper liquidity) but increases the market maker’s worst-case loss. In particular, for LMSR, the standard bounded-loss guarantee is simply \(b\log n\).

2) Order Matching Prediction Markets

We use the umbrella term order matching prediction markets (OMPMs) to describe a broad family of standard microstructures; those where the market mechanism must match each trader with a counterparty, and prices are inferred from the matched orders. These mechanisms are the engine behind today's most popular prediction market platforms (e.g., Polymarket and Kalshi), and the best known member of the family is the central limit order book (CLOB).

Instead of a fixed pricing rule, OMPMs use a collection of standing offers:

- A trader posts a limit order: "Buy \(A_i\) at price \(p_i \le \pi\)" or "Sell \(A_i\) at price \(p_i \ge \pi\)."

- The system matches compatible orders; trades occur when bids meet asks.

Generally, at any given moment, OMPMs imply a piecewise pricing curve from the visible depth, but it does not provide the same kind of global, always-on probability vector we saw in CFPMs. For example:

- If there are no orders, there may be no price.

- Even with orders there may be a wide spread, and the "price" becomes a microstructure choice (last trade, mid-price, best bid, best ask, etc.) made by the platform. Hence "prices", and therefore collective probabilities, may no longer be straightforward to interpret.

- Liquidity can vanish instantly if participants cancel or pull orders, so the mechanism has no built-in "always-on" commitment.

As we'll discuss later, for these reasons and others, trading strategy in OMPMs becomes entangled with timing, other traders’ behavior, and adverse selection.

Examples in "The Wild":

Under the hood, both Polymarket and Kalshi use CLOBs. Some technical details differ between the two platforms, but both also take a centralized approach to matching limit orders.

Surrounding Market Ecosystem

Until now we’ve been treating prediction markets as abstract information aggregators—you define contingent claims, let informants trade, and read the collective forecast off of the prices. Although incredibly useful, in practice, fixating only on the abstraction hides where many dragons reside. A prediction market deployed in practice must bridge two worlds: The clean internal world where the market's mechanics unfold (trades, allocation of shares, price updates, etc.), and the messy external world where events resolve and predictions are interpreted (politics, scientific results, court rulings, etc.).

The moment these worlds collide, hard design questions emerge at their intersection. Nuanced complexity lives where mechanism design's rigor must meld with any imprecision in the domains they're applied to—at the interface between logic and natural language, between off-chain reality and on-chain enforcement, and between how traders interact with a system and externalities it's coupled with.

Microstructure is one of these design decisions, but we discussed it separately as it directly impacts market participants' behaviours and the platforms' decentralization. However, beyond microstructure, we note three platform-level decisions that shape whether markets can remain aligned with the trustworthy information aggregators we were promised during difficult edge cases—or whether they warp into discretionary betting products riddled with "escape hatches" for admins.

Market Topics

Topics specify what markets are trying to predict; in the AD securities framing, it defines the outcome set \(\mathcal{Y}\). Although intuitive at a high-level, natural language is full of edge cases and complexities when paired with context. Questions of the form "Will \(E\) happen by date \(D\)?" highlight this phenomenon well: What counts as "happen", which time zone matters, what data source is authoritative, and what happens if the world produces something adjacent-but-not-identical (e.g., "wins" vs "concedes", "dies" vs "declared dead"). When moving prediction markets from theory to practice, topic design requires products to intermingle with mechanisms; ambiguity is not just cosmetic, and changes incentives while inviting adversarial trading strategies.

Recent Examples:

As we've seen throughout 2025 on Polymarket, these linguistic edge cases not only arise in practice but also take on numerous forms. The "Zelenskyy suit" market left traders in arms about what defines a "suit". The "Astronomer divorce" market presumed the involved couples were married (vs, e.g., common law), and required additional context be added later. Markets whose outcome space need to be mapped to a form convenient for a platform (e.g., scalar predictions are often bucketized to match the "Yes-No" share structure on platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi) can warp trader incentives when their belief doesn't align with buckets and can introduce artificial volatility (e.g., the "April temperature increase" market).

Resolution Mechanisms

Resolution mechanisms determine which claims can be redeemed at settlement; in terms of AD securities, these mechanisms decide which outcome \(Y=y_i\) hold. For some topics resolution is trivial, e.g. an on-chain invariant or a deterministic computation. However, for many topics, resolution reduces to a social choice problem that needs to untangle a web of subjectivity, credibility, and misaligned incentives. A resolution mechanism has to define who can report outcomes, how reports are verified, how disputes work, how long finality takes, and what the system does when reality is genuinely contested. In other words: the mechanism needs to establish a trusted "oracle" that remains credible even when large positions are at stake and adversarial pressures arise. When trust in resolution mechanisms crumble, it impacts not only the contested market but can also indirectly affect how traders will approach future markets.

Recent Examples:

Again, just in 2025, examples abound on Polymarket. The "Ukrain mineral deal before April" market's resolution is widely contested and has resulted in allegations that their resolution mechanisms were manipulated. Similarly, the "Fordow nuclear facility destruction" market remains contested as the involved countries reported differing outcomes and no neutral third party was granted access.

3) Commitment Protocols

Predictions are often contingent on a very specific set of priors, and commitment protocols serve to give traders "alignment" on those priors by defining what is locked once a market goes live—topic wording, data sources, dispute rules, settlement rules, fee schedules, discretionary powers held by humans or governance, etc. For prediction markets to serve as well-designed information aggregators in practice, commitments are not optional niceties; they are a market’s cornerstone. Traders will calibrate their beliefs subject to these commitments, and these commitments have deep implications on how effectively information can be injected into markets. How an event is interpreted, the integrity of the mechanism that adjudicates it, etc. all inform trading strategies and, in turn, the information contained in each trade. If critical terms can change after positions are established, then the "market price" is no longer a clean forecast; it is entangled with governance risk, admin risk, and meta-speculation about how the platform will behave under stress. Commitment protocols are often hidden under other platform-level decisions (or altogether overlooked) in discussions about prediction markets, but end-to-end commitments need to be made explicit in these complex systems or else rational actors will seek out unexpected ways to trade accuracy for profit seeking.

Examples in "The Wild":

Continuing with our examples on Polymarket, their commitment protocols are essentially folded into various design decisions and relatively opaque. A market's rules are posted with the market page's creation, but almost every facet of the market can be "clarified" (aka "changed" or "amended") right up until the final resolution. In some cases, the tradable outcomes in a market can change mid-flight or they can all be effectively nullified (e.g., if the determined outcome is unknown/50-50) at settlement. Even the resolution mechanisms, which are committed to in theory, rely on human discretion (from UMA token holders, evidence submitters, etc.) and are so malleable that they can be influenced while markets are live. The lack of explicit and well-defined commitments gives rise to a class of mechanism-aware trading strategies that aim to explicitly capitalize on these uncertainties rather than introducing information to markets, e.g. the "dispute alpha" strategy.

In Conclusion...

We introduced prediction markets with a skew towards future discussions in this post. This is intentional, and our introduction is by no means comprehensive. Prediction markets have been studied extensively and, depending on your focus, can be compartmentalized into a much more granular framework. For readers interested in diving into this rabbit hole, I suggest the following:

- If you want a more philosophical/theoretical survey of prediction markets and their design objectives, then this survey from 2010 is a great starting point.

- If you want a practical and more systematic decomposition of the design space for prediction market platforms, a recent systematization-of-knowledge paper breaks decentralized prediction markets into a seven-stage workflow. Their analysis of these systems is broader and aims to categorize rather than fix, but I believe their systemization is both useful and insightful for readers interested in the topic.

Alternatively, although out of scope for this post so I left it out, wagering mechanisms are a very related class of mechanisms that're generally under-represented in conversations about aggregate forecasting. These mechanisms have shared ancestry with CFPMs, but are built with slightly different assumptions about the aggregator and how informants want to participate. I'll probably write a seperate post at some point about wagering mechanisms and forecasting tournaments, but this paper can serve as a nice introduction to the topic although not being a survey per se.

In what's coming, I'll leverage the ideas and tools we highlighted here to analyze real world prediction markets and the platforms they exist inside of. As many readers will have noted, the platform-level decisions we've introduced are tightly coupled—a topic is only as good as the resolution mechanism that can adjudicate it, and a resolution mechanism is only as credible as the commitments preventing it from being swapped or pressured ex post. The inter-relation between these decisions is precisely where many dragons live, and is a focal point of our upcoming discussions.

Part II:

The On-Chain Prediction Market Thesis

When prediction markets first entered the blockchain technology zeitgeist in the early 2010's, they promised to be much more than some variant of "a decentralized gambling app". They embodied something closer to a public utility:

A mechanism that turns earnest belief into a collective forecast—without requiring anyone to trust the operator.

The Markets We Were Promised

The Ethereum whitepaper states the core intuition behind this thesis quite casually; with an oracle (or a oracle-like Schelling mechanism), prediction markets are "easy to implement" and might even become a mainstream substrate for futarchy. The claim here is not that prediction markets are trivial, but that the blockchain provides the missing enforcement layer—collateral can be escrowed, payouts can be executed mechanically, and participants don’t need to grant discretionary power to an intermediary.

A decade later, the most prominent prediction markets have indeed shown flashes of that promise, and Vitalik’s more recent "info finance" framing captures the significance. His argument boils down to something along these lines:

Prediction markets don’t just serve the traders placing bets, they can serve everyone who reads the charts. Markets become a unique kind of informational public good—a way to compress scattered signals into a continuously updated, legible forecast. Crucially, the value is not limited to a handful of headline events; the long-term opportunity is a world of "micro" questions—myriad small, targeted markets designed to extract specific facts, judgments, or conditional predictions—if the underlying substrate and participants can support it.

The thesis was never merely to "put these markets on a blockchain" or "allow people to gamble on future events". It was to use blockchains to make prediction markets credible by construction. To enable markets that anyone can access, that no one can rewrite at their discretion, and that verifiably settle according to rules that were committed to before the money arrived.

This thesis is easy to get behind in the abstract, but once you begin writing it down as concrete technical requirements you begin to see the silhouette of dragons rising on the horizon. Avoiding these dragons is why so many attempts retreat into permissioned market creation, discretionary resolution, governance-supported backdoors, and non-commital liquidity provisioning. These dragons are not philosophical; they are implementation details that bite, but I believe they're surmountable with modern techniques and conviction (more on this in Part V).

The Properties We Should Demand

If we want to build prediction markets that serve as the public utility we've envisioned—and not as a permissioned version designed around the goals of platforms themselves, their liquidity providers, etc.—then decentralized prediction market platforms need to satisfy a set of axiomatic properties and make strong, principled commitments. These are not for aesthetics, but rather they're invariants needed to keep the system honest when incentives turn adversarial, edge cases arise, and circumstances no longer serve specific stakeholders.

1) Permissionless market creation, with enforceable topic guardrails

A central part of the promise is that "anybody can create a market", but it is critical that we're realistic that "anything can be a market topic" is an ethical and legal minefield. For a platform to credibly support permissionless market creation it needs a way to support open creation while constraining the space of allowable topics such that it doesn’t reintroduce human vetoes as a central point of failure. In practice, this means markets must be specified in a algorithmically-verifiable format (clear outcome set, timeframes, data sources, etc.) and topic restrictions must be enforced by protocol-level constraints (or, at least, by constraints that are themselves credibly neutral and not manipulable ex post).

2) Always-on liquidity with committed capital

A prediction market that has no price for long stretches of time is not aggregating information; it is intermittently hosting bids and asks. Ensuring coherent probabilities throughout the entirety of a market's lifespan requires an always-on pricing mechanism and a liquidity commitment structure that prevents rational liquidity from evaporating precisely when the market becomes most informative (near resolution, under controversy, etc.). The design goal doesn't equate to having deep liquidity, but rather to ensuring liquidity cannot disappear (strategically, arbitrarily, or otherwise) after other participants have relied on it.

3) Prices moved by beliefs, not microstructure meta-strategies

A well-designed and efficient prediction market should make being right the reliable strategy for making money. In other words, the marginal P&L of a trade should be driven mainly by the gap between your belief and the current implied probability—not by your ability to harvest spreads, rebates, queue position, latency, or temporary price voids. Importantly, this doesn't mean eliminating arbitrage in the broad sense; some arbitrage is healthy as it enforces logical coherence across related markets (e.g., "A or B" vs "A" and "B"). Our target here is much narrower, we want markets to facilitate a contest of research and calibrated beliefs rather than rewarding strategies based on timing, execution, and structural quirks.

4) Precommitted resolution that is reproducible and tamper-resistant

All roads lead to resolution in prediction markets, and resolution mechanisms can color or even kill these markets in practice. If the resolution mechanism can be swapped, influenced, or "interpreted" after positions are established, then trading ultimately reduces to governance speculation. To reliably aggregate signals throughout a market's duration, a platform must commit—at market creation—to a resolution mechanism that is: specified in advance (including dispute handling and tie-breakers), reproducible (third parties can independently replay and verify the outcome), and credibly resistant to manipulation by the market creator, the platform operator, or any "council" that can be captured.

5) Automatic settlement triggered by the resolution mechanism

Settlement is the end of the causal chain cementing a market's incentives. If resolution produces an outcome but settlement requires human approval (signing a transaction, blessing a payout, etc.), then the platform has reintroduced a trusted intermediary at the final step. The property we need is simple: resolution implies settlement. Once the precommitted resolution mechanism finalizes, redemption should be directly and automatically enabled (or executed) by the same rules that were locked in when the market was born.

6) Credible neutrality over the full lifecycle

Even if all these properties are satisfied on paper, decentralization fails if the platform can censor participation, delist markets, change fee schedules, pause trading, or unilaterally rewrite contracts through upgrade keys. These may sometimes be defensible product choices, but they are also governance levers—and governance levers become attack surfaces when money is on the line. Once a market is created, its terms are final and sacred; it must run its course until predefined finality conditions are satisfied, and without exception.

In Conclusion...

Taken together, these properties serve as a north star that guide us towards the prediction markets we were promised: An always-on probability layer that can’t be leaned on by insiders, that can’t be rewritten by governance once started, and that settles by construction rather than by permission.

These properties, and building the ideals in this thesis, underlie the analyses and arguments we make throughout this post. In particular, our next part will look at how existing prediction market platforms measure up against these properties.

Part III:

Praxis and the Illusion of Progress

On the surface it's easy to look at the last few years of prediction markets and assume that "the thesis is working". Compared to earlier platforms (e.g., Augur) the interfaces are smoother and the liquidity is thicker in flagship markets. Charts from platforms like Polymarket and Kalshi have broken into the mainstream; they circulate on social media while being cited by politicians and pundits in the same breath as polls. A decade ago this would have sounded like fiction. However, most of the progress towards the thesis is exactly that—surface-level smoke and mirrors. While the UI has improved, the underlying infrastructure—what blockchains were supposed to make credible by construction—has gradually centralized.

In this section we’ll take a step back and look at modern platforms and how they measure up against the properties we previously set forth. We’ll look at where they concentrate control—market creation, liquidity provision, resolution, settlement—and how those concentrations predictably surface as inefficiencies, fragility near resolution, and exploitable opportunities whenever disputes are likely.

Whose Discretion Matters After Positions Are Established?

The "control surface" of prediction market systems in practice can be understood along four axes:

- Market creation \(\rightarrow\) Who can define what is being predicted? Under what Constraints?

- Liquidity \(\rightarrow\) Who ensures prices exist? What stops liquidity from disappearing when inconvenient for liquidity providers?

- Resolution \(\rightarrow\) Who decides what the outcome is? Using what evidence? What are the rules for disputes? What guarantees do we have?

- Settlement \(\rightarrow\) Who triggers or enable payouts? Can anyone block, delay, or rewrite it?

Platforms can call themselves "decentralized" while still centralizing along any of these axes, but if any facet within (or even between) these is mutable ex post—i.e., once money arrives and there is skin in the game—then traders are no longer making decisions based purely on their beliefs about what'll happen in the world. Instead, trading is (and rationally should be) driven by beliefs about a mixture of reality and platform behaviour under stress. The market prices in such a system cease to be the clean forecasts promised by the thesis; they become a noisy composite signal contaminated by meta-speculation about how the system behaves at critical junctures.

Given the intensity of these statements, I want to make two points clear. Firstly, modern platforms absolutely do aggregate information and can yield useful forecasts. Secondly, what follows is not an indictment of any single platform. Rather, I'm making claims about design attractors that I believe existing platforms are being pulled towards and that ultimately are self-defeating if our goal is to build towards the thesis. The uncomfortable truth is that today’s prominent platforms are not early versions of what'll lead us to the "info finance" ideals that drive the zeitgeist. They are, increasingly, a different product category—one that converges toward gambling-like incentives and systemic choices favoring specific stakeholders while siphoning credibility from a well-intentioned thesis.

A Diagnostic Lens: Looking Along the Axes of Control

To make this analysis concrete, it'll help to briefly reframe the properties we demanded previously as operational questions:

- Can anyone start a market without permission—and are topic guardrails enforced by protocol or human veto?

- Are probability vectors well-defined throughout the market's lifespan, and can liquidity be withdrawn once others have relied on it?

- Are prices being moved by traders' beliefs about the realized outcome, or by their understanding of the platform's behaviours?

- Is resolution explicitly precommitted, reproducible, verifiable, and tamper-resistant?

- Does resolution mechanically imply settlement, without a final discretionary signature?

- Is the system credibly neutral over the full lifecycle of the market, or can it censor, pause, delist, amend, or rewrite?

Many modern platforms provide compelling answers to some of these questions—especially when it improves UX, reduces operational risk, or maximizes profits. That said, answering the questions that matter most for enshrining credibility by construction are usually left as an afterthought and are where centralization creeps in. We'll see why as we follow the four control axes that platforms tend to design around.

Market Creation: Permissionless in Marketing, Permissioned in Protocols

A truly open substrate for prediction markets is structurally incompatible with "predict anything" if it's meant to exist in the real world. This isn't a moral stance, it's a systemic reality. Allowing unconstrained creation of market topics invites markets that are unethical, illegal, coercive, or violent—markets whose existence creates negative externalities even if they never settle. Any platform that wants to exist within (and preferably contribute to) society must confront this.

Ultimately, prediction markets are tools for information aggregation and, like all tools, are not appropriate for all jobs. Hence keeping our trajectory aligned with the thesis doesn't require ensuring "can anyone create a market on any topic"—it's requires solving "how do we design robust systems that allow anyone to create a market within a class of topics we're able to support". The distinction between these two problems is often conflated and misrepresented in standard talking points about prediction markets, and designing products to maintain the illusion that your platform supports "markets on any topic" will culminate in fundamentally different technologies. The complexities of scoping and enforcing market topic guardrails is the first dragon that platforms often confront, and beware because it's one that'll rear its ugly head throughout our discussions below.

With this intuition in mind, the bifurcating decision becomes how topic constraints are enforced: Protocol-enforced topic guardrails are automated constraint systems that are legible, checkable, and binding; they restrict what can be expressed (or at least what can be instantiated) without depending on any operator's discretion after the fact. By contrast, platform-enforced topic guardrails require discretionary review by some trusted party and, even if the trusted party is well-intentioned, the existence of a veto is an inherently centralizing force.

The most prominent platforms almost always choose platform-enforced guardrails, e.g. market creation on Polymarket and Kalshi. They curate markets and narrow what can be created by relying on internal policy, compliance review, and editorial judgment. That choice is understandable—and often legally necessary—when the goal is to present yourself as enabling "markets on any topic". Unfortunately, this choice also has deep downstream consequences, as the platform effectively becomes both the editor and the publisher of reality's questions; it can no longer serve as a neutral substrate.

In this newfound dual role the platform becomes a bottleneck and must optimize accordingly to survive. The goal is no longer to support and facilitate markets that maximize informational value. It necessarily becomes to optimize for attention, retention, controversy, repeat trading, etc. while simultaneously ensuring markets remain within operational and legal risk thresholds.

Once the system is built around platform-enforced topic guardrails its center of gravity shifts by construction. The informational public utility we were promised wants a long tail of micro-markets and niche questions, whereas the platform businesses that dominate today need a manageable catalog of high-volume and high-engagement markets. Historically, attempts have been made at building platforms with protocol-enforced topic guardrails (or lack of guardrails), but the class of topics they support are either extremely narrow (e.g., Thales) or again "markets on any topic" (which runs into rather predictable pitfalls) .

Interestingly, the dragon we see here is surprisingly straightforward to rout if we confront it methodically and with conviction. Sailing around this dragon by resorting to platform-enforced guardrails will leave your platform ill-equipped when it confronts subsequent threats. Confronting it recklessly, without appropriate defenses, by naively scoping the class of markets your platform can handle will kill your platform outright or leave it debilitated. In either case, the lesson is simple: A platform without appropriate scope and guardrails for market creation can easily start looking less like "an information aggregator for the people" and more like either "a den of thieves and assassins" or "a bookie for whatever is currently legible, tradable, and safe enough to host".

Liquidity: Available When Convenient, Absent Otherwise

Beyond market creation we must confront questions about liquidity, where a platform's true commitments are revealed.

In our post introducing prediction markets, we highlighted two popular families of market microstructures: cost function prediction markets (CFPMs) and order matching prediction markets (OMPMs).

In CFPMs, liquidity isn't something you hope for; it's contractually cemented at market creation. Prices exist because the mechanism provably guarantees they exist, and if you want to move probabilities then you can always do so at a well-defined cost. Critically, once capital is committed in a CFPM, it serves as a market parameter that cannot evaporate when conditions become adverse.

Despite these strong liquidity guarantees, CFPMs are not used by popular prediction market platforms today—OMPMs are undisputably the dominant microstructure choice. These platforms use CLOBs where bids and asks appear and disappear at the will of participants (or a small set of professional market makers). Despite their popularity, order matching has two immediate side-effects: Prices aren't guaranteed to exist (especially in thin markets) and can have unintuitive probabilistic interpretations. Liquidity is least reliable when adverse selection spikes because rational liquidity providers widen spreads, reduce size, or pull orders.

The adoption of OMPMs on these platforms is not a consequence of any high-minded principle or technical superiority; in fact, it'd fair to say that CFPMs have stronger economic guarantees and more rigorous underpinnings. The ubiquity of OMPMs is almost certainly rooted in their lack of risk for platforms while simultaneously appealing to professional market makers whom platforms (with their newfound role as "publishers") want to attract. At the end of the day, microstructure is not an implementation detail. It's a decision about who the market rewards and who takes on risk.

As we've discussed at length, a prediction market mechanism that reliably aggregates information should reward traders for being right about the world. Yet profit opportunities in OMPMs often come from being right about market flow; anticipating other traders’ timing, harvesting spreads, exploiting latency, or positioning around liquidity vacuums.

To be clear, I'm not claiming that professional market making is evil or has no place. I also believe OMPMs can be well-suited microstructure choices for specific markets where sufficiently high-volume, high-engagement, tight spreads, etc. are reasonable assumptions. However, in general, prediction market platforms accommodate a long-tail of thin markets, which are precisely the settings where reliance on a small set of actors who are not committed—actors who can enter and exit at will—results in markets that become least liquid precisely when they're most informative. In other words, these platforms become venues whose informational capacity is contingent on voluntary, profit-maximizing liquidity that can leave whenever the venue becomes stressful.

Liquidity without commitment is a mirage, and a prediction market without liquidity is a hollow facade. Confronting inconvenient facets of liquidity provisioning in prediction markets is the second dragon platforms face; high-quality information has a price, and somebody has to be committed to paying that price for prediction markets to function as intended in thin settings. When we refuse to confront this dragon, and utilize microstructures poorly suited to the settings we deploy prediction markets in, our information channels become noisy (or entirely unreliable) and undermine the quality of the forecasts produced.

Resolution: Locked in Principle, Fickle in Practice

For prediction markets to elicit the trader behaviours they're designed around, everything must converge to resolution. Although damaging, a prediction market can survive thin liquidity. It can survive clunky UX. It can even survive a messy topic definition if the resolution is unambiguous and credibly enforced. However, although resilient, a prediction market cannot be expected to serve its purpose if resolution becomes discretionary after positions are established; such a market stops being about the topic being predicted and becomes about the system.

The biggest platforms today (e.g., Polymarket) resolve via some combination of human interpretation of rules, discretionary "clarifications", token-holder (or stakeholder) voting in an oracle game, and dispute processes that depend on who shows up.

These mechanisms can work in the sense that they usually produce an outcome, but that's an insufficient metric for success in resolution mechanisms being deployed in markets with real money, entangled incentives, and externalities. When designing an resolution mechanism for prediction markets, the objective was never simply "get an outcome". It is to get an outcome via a mechanism that is at a minimum: precommited upon market creation, reproducible a posteriori, verifiable by third parties, and resistant to capture when stakes are high.

Satisfying all of these objectives in tandem is hard, or arguably impossible, for most topics where resolution requires an interface with the outside world. Praxis tends to override the thesis here, and it's hard to give platforms a good finger wagging when you lack a strongly justifiable alternative. In turn, many platforms have embraced oracle designs that're good enough most of the time while satisfying additional properties that're desirable for themselves (e.g., "escape hatches" under sufficient blowback) and their users (e.g., fast resolution).

The end result is platforms relying on oracles that are more political than mechanical, more malleable than topics typically require, and designed under trust assumptions ill-suited (e.g., dependent on individuals' influence or patience) for the scales markets see today. Notably, these oracles are incompatible with the thesis the moment they allow discretionary change after meaningful open interest accumulates in a market since the platform has functionally introduced a new tradable asset—governance and interpretation risk.

A standard response to my critique might be "we need flexibility because natural language is messy". This is absolutely true...if you insist on building platforms that attempt to support "markets on any topic". Moreover, even if that is true, we should at least be honest about what we've built. We haven't built an oracle that makes truth legible on-chain, we've built an institution that interprets truth under incentives. In practice, regardless of how elaborately we dress them up in crypto-jargon about decentralization and trust, we've reintroduced a trusted intermediary in the moments it is most profitable to be one.

In markets where predicting the topic outcome is harder than predicting systemic behaviours, sophisticated traders focus on the latter; their strategy is a natural equilibrium response when resolution is not credibly locked. Therefore, to remain on a trajectory aligned with the thesis, we must design systems that aim to ensure that "predicting the system \(\approx\) predicting the topic outcome".

At this point it may seem like we've encountered an insurmountable dragon, but I disagree wholeheartedly. At a surface level it may sound like I've presented a critique inherent to these oracles; this is only true when we hold everything else fixed. As previously mentioned, prediction markets are tools and tools should be used where appropriate. The oracles used today require humans and those humans can participate in prediction markets, so incentives for earnestly performing your duty in the oracle can degrade dramatically when prediction markets reach a certain scale—platforms have indirectly incubated this dragon due to their own mainstream success, and they're now being forced to confront it. We're thus presented with three forks in the road: Recalibrate incentives (unrealistic and unsatisfactory), abandon the thesis (unsavory and socially damaging), or solve the problem (worry not, more on this in Part V).

Settlement: An Off-Ramp by Design, A Gatekeeper by Implementation

Even with well-defined resolution mechanisms having all the properties we can dream up, settlement can reintroduce trust on the way out. Platforms can satisfy the thesis from creation through resolution, and still rely on a final discretionary step for payout—a multisig, an operator transaction, an admin-controlled contract, a custodial ledger, or a centralized exchange mechanism that is ultimately enforced by internal databases rather than by on-chain settlement.

Why would this ever happen in practice? Intuitively this seems easy to avoid, and like a ridiculous obstacle to get tripped up on right at the end. The answer is painfully straightforward once we remember that modern systems exist in the real world while maintaining the illusion of having "markets on any topic": If your platform has taken on that role of a publisher and editor, then settlement is where operational and legal risk concentrates. (You were warned that dragon would keep rearing its head...)

When your platform gatekeeps market creation and encourages inappropriate or maliciously defined topics, then you better be able to delay settlement, freeze it, or apply exceptions to protect yourself when the unexpected (expectedly) happens. This becomes doubly the case when your goals as a "publisher" incentivizes you to push boundaries in pursuit of intrigue and spectacle.

From the perspective of the thesis, this is both entirely avoidable and absolutely fatal. If settlement requires permission, then these prediction markets are not mechanisms that settles by construction. It is a product that settles by permission, and whose payouts are contingent on an operator’s willingness (or ability) to execute them. The moment users internalize that possibility—even as a low-probability risk—it implicitly bleeds into the forecasting task. As we've repeated ad nauseum by now, a probability that includes the chance a platform will intervene is not a probability of the external event; it is a probability of some calibration about the event and of a platform-mediated payout event.

A Case Study: The Augur Post‑Mortem Fallacy

To help make these diagnoses more concrete, let's revisit a well-known early example in the history of prediction market platforms: Augur.

Thus far we've talked about the four control axes as if they're independent, but in reality they’re entangled. Open-ended market creation changes what "liquidity" means, topic ambiguity eventually spills into resolution, and slow resolution becomes a settlement problem. Augur exemplifies this coupling "nicely".

They tried to take the early thesis literally: Anyone could create a market on almost anything, markets traded on an order book, outcomes were resolved by an on-chain dispute game, and payouts were enforced by "code is law". For a moment, it may have even looked like the promised neutral substrate. However, its slow demise isn't from any one isolated dragon—it was these dragons reinforcing one another throughout the whole control surface.

We'll first consider the interaction between their choices surrounding market creation and liquidity. They went with "anyone can make a market" while also utilizing a CLOB as their microstructure, which results in a system that ensures anyone can fragment attention. When markets proliferate, the platform splinters into a long tail of thin books; in those settings a CLOB often has no meaningful price at all. The natural-but-wrong takeaway was "we need more volume". However, the more accurate takeaway is "order books need concentrated two‑sided flow", so a platform that encourages a long tail of user-defined markets needs (i) a microstructure/liquidity model that degrades gracefully in thin settings, and/or (ii) topic constraints that actually let attention concentrate.

Next, we'll hone in on the interaction between market creation and resolution. Augur allowed markets to be created using essentially unconstrained natural language, which gave them "expressiveness" in exchange for ambiguity, hard-to-detect duplicates, and adversarial markets. Not only did this hurt UIs built around Augur, the ambiguity resulted in a surge of costly disputes; resolution was often slow and socially exhausting.

Lastly, Augur's pipeline for market creation, resolution, and settlement created friction together. Slow resolution slows settlement down too, and similarly their gameable resolution mechanisms in turn made settlement gameable. Augur’s history includes "invalid market" dynamics where market creators exploited subtle inconsistencies to steer toward an "invalid" resolution, which changed payoffs in ways unprepared traders didn’t anticipate. So we saw that, even if specific components are nominally on-chain, the system can still produce outcomes that feel like rug pulls because the binding contract is the mechanism and not the plain English topic description.

In a sense, modern platforms seem to have arisen as a "minimum-change" response to Augur—they keep the familiar CLOB experience, concentrate liquidity by managing a catalog of high-engagement markets, and smooth over resolution/settlement with institutional processes that can move quickly under stress. The industry seems to have looked at Augur's mistakes and saw a set of single-axis lessons, but this led to incomplete conclusions; they fixed CLOBs with more volume, fixed the unconstrained topic problems with moderation, and fixed resolution speeds with discretion. By contrast, if you take a step back and look at Augur as a coupled system then different lessons fall out:

- Microstructure needs to match topic scope. If you want a long tail of niche markets, then a pure CLOB is brittle without explicit liquidity commitments.

- Guardrails are not synonymous with editorial discretion. Building appropriate topic guardrails is a protocol design problem, whereas curating topics is a business decision.

- Speed can’t come from opaque malleability. If your resolution is too slow because of disputes, then speeding it up by making it malleable and discretionary after money concentrates isn't addressing the root cause.

Ultimately, building around incomplete conclusion clearly made the product work—but it also tightly wound the coupling until a new set of incentives formed. Which brings us to the next section: The gambling attractor isn’t a moral failure or a branding choice—it’s the equilibrium you drift toward when the easiest way to survive is to dance around the dragons rather than slay them.

The Gambling Attractor: Exchanging Truth-Seeking for Profits

Now that we've laid out the dragons that live enroute to building a prediction market platform, we're ready to say the quiet part out loud. When we embark on this journey, there are two clear attractors we can expect to reach:

- A platform sustained by the informational utility it provides and the ideals it enshrines.

- A platform sustained by the entertainment it provides and the profit it ensures for stakeholders.

The former corresponds with building towards the thesis, but is technically more difficult to implement and requires practically unbudging resolve. The latter corresponds with building while sailing around the dragons we've identified, and is unfortunately much easier to arrive at.

The point I've been making is not that any one choice that steps away from the thesis is inherently "bad". It's that each choice is a perfectly rational response to operating a platform as a business under real constraints. Once made, those rational responses gradually become entrenched as the platforms grows and infrastructure is built, which systematically moves platforms away from the promises they set out to fulfill. With time the economic incentives of the dominant platform model pushes prediction markets towards gambling even if everyone involved sincerely believes in the ideals laid out in the thesis.

In Conclusion...

The criticisms we've laid out are not an inevitability, they're a diagnosis we can systematically unravel and address. Building prediction market platforms without compromising ideals doesn't require philanthropy nor altruism, it just requires a strategy and innovation using modern tools that have only recently come into existence.

Some readers may wonder whether the concerns here are just pedantry, but it is important to remember that these influences compound and become self-reinforcing with the many factors we've discussed. Taken together, polluting the channel of information while eroding (or altogether replacing) the pillars our thesis is built atop is how we accidentally transmute forecasts into casino chips.

So what should we conclude? Well, in my opinion, it's that modern mainstream platforms are not slowly approaching the original on-chain thesis; they're optimizing toward a different equilibrium.

The stage is now set for the question we'll focus on for the rest of this series:

If the dominant branch of the prediction market platform ecosystem will keep sailing around these dragons—because it is rational to do so—what would it take to finally slay them?

Over the next few days we will continue to update this post. We've introduced the prediction markets we were promised, and now we'll look at the dragons in our way. Next time we'll figure out how we might slay them.